Two must-reads

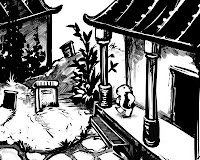

Now that the brilliant Ursula Vernon has made Digger freely available online, I've been catching up (previously she had the site hosted on a webcomics site that was part-free/part-subscription, and I never quite had it in the budget to subscribe for one comic, however awesome). I've possibly recommended Digger before: the epic and comic tale of a very secular wombat who finds herself emerging from a hole in a temple of Ganesh, pursued by the servants of a buried-and-chained living dead god, Digger is far better read than described; it truly is a rich, smart, funny beautiful piece of work, one that's a ready example of how comics in general and webcomics in particular are an art and not just some kind of funnybook for people who can't handle novels (most of which lack the sophistication and depth of something like Digger, I might add).

Now that the brilliant Ursula Vernon has made Digger freely available online, I've been catching up (previously she had the site hosted on a webcomics site that was part-free/part-subscription, and I never quite had it in the budget to subscribe for one comic, however awesome). I've possibly recommended Digger before: the epic and comic tale of a very secular wombat who finds herself emerging from a hole in a temple of Ganesh, pursued by the servants of a buried-and-chained living dead god, Digger is far better read than described; it truly is a rich, smart, funny beautiful piece of work, one that's a ready example of how comics in general and webcomics in particular are an art and not just some kind of funnybook for people who can't handle novels (most of which lack the sophistication and depth of something like Digger, I might add).But heralding Digger is actually only a small part of the reason for this post; as it happens, a portion of Digger draws upon a really amazing six-page Miami New Times article from June, 1997. Lynda Edwards' "Myths Over Miami" describes how the homeless children of the Miami shelters were (and perhaps still are) crafting a complicated mythos to explain their history and future, succumbing to the basic human needs to tell stories and to impose order on chaos by cobbling together story-cycles based on pop-culture, half-understood fragments of mainstream religion, rumors, and their own imaginations.

One demon is feared even by Satan. In Miami shelters, children know her by two names: Bloody Mary and La Llorona (the Crying Woman). She weeps blood or black tears from ghoulish empty sockets and feeds on children's terror. When a child is killed accidentally in gang crossfire or is murdered, she croons with joy. "If you wake at night and see her," a ten-year-old says softly, "her clothes be blowing back, even in a room where there is no wind. And you know she's marked you for killing."

The homeless children's chief ally is a beautiful angel they have nicknamed the Blue Lady. She has pale blue skin and lives in the ocean, but she is hobbled by a spell. "The demons made it so she only has power if you know her secret name," says Andre, whose mother has been through three rehabilitation programs for crack addiction. "If you and your friends on a corner on a street when a car comes shooting bullets and only one child yells out her true name, all will be safe. Even if bullets tearing your skin, the Blue Lady makes them fall on the ground. She can talk to us, even without her name. She says: 'Hold on.'"

One can't help thinking of one of the more effective set-pieces in the mostly-mediocre 1985 Mad Max installment, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome--a tribe of orphaned children telling stories about creation and salvation in a post-apocalyptic outback. The whole bit in the movie is, on one level, a goofy plot twist wedged into an overstuffed movie to try to motivate the normally antiheroic title character, except that the sight of these kids actually telling stories about the how and the who and the what of themselves ends up being uncannily effective in spite of itself. More ironically, in light of the New Times piece, it ends up being surprisingly real; the urge to explain the hopelessly inexplicable begins early, it seems, and the homeless children of Dade County, with their mentally-ill and drug-addicted parents and complete lack of stability have many more inexplicable things to reckon with, live in a world that requires much more imposition of will to mold into something that makes any sense, and even so what sense it makes is terrible and tragic. The Blue Lady's true name, which will save the faithful from gangbangers' stray rounds, turns out to be unknown and held secret even from the believers.

Read the New Times piece, even if it's the only online article you read this weekend.

And if you have time left over, get yourself addicted to Digger.

Comments

It makes me reflect on Jung, the collective unconscious, and the recurring nature of myth in different cultures and times. (Campbell, anyone?)

There's a seed of a really interesting story there if I can work it out.

This is probably the missing piece I need to add to my Fringe Runners -- sort of outlaw nomads on the edges of human space in my 29th century universe. They started out as the bogeymen you'd tell your kids about, then a thorn in the side of the colonists and the military. Then I've made them both more organized and less monolithic, so that the Runners don't understand why people label them with one brush. And lately they've actually been allies with the military against the aliens -- their people are dying in the war, too. Now they need their varied mythos, which the "regular" people fail to notice or understand.

Nice.

Dr. Phil